Even though I’ve only been in Galápagos for all of an hour, it already feels like the world I came from is a lifetime away. Along with my fellow passengers, I’ve climbed into the small, panga-style boat as we’re shuttled from the docks to the yacht that will be our home base over the course of a weeklong cruise experiencing these unique islands.

The water of the bay in San Cristóbal, the easternmost island of the Galápagos archipelago, is cool and clear. The day is warm, a touch of humidity in the air. As the panga makes its way across the water, we pass what looks like an abandoned fishing boat—abandoned by people, anyway. The four or five sea lions lazing on its surface tilt their heads toward us with only the mildest of interest before returning to their sunbathing.

And then our destination comes into view: the Grace, a motor yacht operated by Quasar Expeditions, stands out from the rest of the vessels on the bay.

As I climb on board, I’m immediately struck by the yacht’s striking yet understated elegance reminiscent of, say, a Golden Age of Hollywood icon and literal royalty. Of course, that may have something to do with the fact that Grace Kelly and Prince Rainier III of Monaco actually honeymooned on the very same vessel. And while this single chapter in the Grace’s history would be intriguing enough, underneath the yacht’s refinement is an even scrappier, more thrilling story.

Recommended Fodor’s Video

After the Grace (known during those years as the Rion) was completed in 1928, she enjoyed a decade or so of leisure before conscripted into the British war effort. Equipped with guns and cannons, the repurposed yacht survived fighter plane attacks, the Battle of Dunkirk, and played host to Winston Churchill. As a backdrop for a Galápagos adventure, the Grace is impressive, to say the least.

But, when it comes to the Galápagos, this outsized history is by no means limited to one vessel. The Grace and its whirlwind story are entirely emblematic of how any given moment in this place can feel big and strange and wondrous—often all at the same time. Indeed, there seems to be something about this remote collection of islands that fosters the rare, the peculiar, and the fearless. A heritage that the archipelago's history reflects all too well.

3-5 Million Years Ago. Volcanic Formation

“The sun turns black, earth sinks in the sea,

The hot stars down, from heaven are whirled;

Fierce grows the steam, and the life-feeding flame,

Till fire leaps high, about heaven itself.”

—Völuspá

The ground under my feet feels brittle, almost hollow somehow, as I walk across the lava flow on Santiago Island, one of the main islands situated near the middle of the archipelago. The frozen folds of blackened, hardened terrain start at the shoreline and spread out as far as the eye can see. And while it feels as if I’m trekking across some sort of prehistoric landscape, the lava field is relatively young, having formed after a volcanic eruption in the late 19th century.

The twisting texture of the lava flow isn’t just a fascinating locale, but a window into the very inception of the Galápagos islands.And what better way to kick off a larger-than-life history than with the most dramatic of beginnings—the volcano-based kind. The Galápagos islands were formed by a hotspot (a geological term for volcanic regions that are fed magma and not, say, a trendy nightclub) located on the border of the Nazca and Cocos tectonic plates. As the volcanos erupt the layers of volcanic material build up toward the surface until—voilá!—an island is shaped. The process repeats itself as the tectonic plates shifts, forming the rest of the islands in the chain.

It’s believed that the oldest of the islands were formed 5 million years ago and the most recently came into being around 3 million years ago, making the Galápagos islands spring chickens by geological standards.

The tradition of volcanic activity has carried on through the Galápagos’ with Wolf volcano, located on Isabela, the largest of the islands, erupting as recently as May 2015.

17th Century. Here Be Pirates

“Now take Sir Francis Drake, the Spanish all despise him, but to the British he’s a hero and they idolize him.”

—Muppet Treasure Island

It’s so tempting to mistake Española, the oldest island which occupies the southwestern most corner of the archipelago, as some kind of tropical paradise. The place where we made our landing is pristine, the crystalline water lands in lazy waves on the sand while sea lions sunbathe and nap. An extroverted Galápagos mockingbird keeps positioning itself in front of me, insistent on being Instagrammed. There’s even a banner of green flora not far from the beach.

But as I follow the rocky path inland, the greenery quickly gives way to very spare, shoulder-high bushes. The branches are skeletal, sapped to a muted brown. The landscape is dry, even by Galápagos standards, only receiving a couple of inches of rain a year. As bewitching as the beaches and our friendly animal welcome party have been, it doesn’t take long to see the stark, challenging side of the Galápagos.

Indeed, throughout the earliest chapters of the Galápagos’ history, its remote location and few fresh water sources ensured that no one ended up there intentionally. While some scattered evidence has been found of Incan people visiting the islands, it’s believed that the Galápagos’ earliest visitors were primarily lost or waylaid.

It wouldn’t be until the Golden Age of Piracy that visitors willing to meet those challenges head-on would frequent the Galápagos’ shores.

During the 17th century, pirates became a common fixture on Spanish trade routes—particularly on South America’s western coast. And when it came to finding a place to lay low post raid, the Galápagos’ made for an ideal hideout. The islands were close enough to mainland Ecuador that British buccaneers could raid Spanish ships with relative ease but distant enough that they were able to retreat and evade capture. During this time, the islands would play host to such esteemed renegades as Sir Richard Hawkins, Sir Henry Morgan, and Sir Francis Drake.

The lack of fresh water wasn’t as tricky an issue since they weren’t planning on staying long anyway. (Though they did take the time to carve massive statues to scare off any interlopers who happened to get too close to their stores of supplies and gold.) Plus, they could feast on the readily abundant meat of the giant tortoises. Indeed, buccaneers and the whalers that followed them ate so many tortoises that their population had been severely depleted by the time Charles Darwin made it to the islands in the mid 19th century.

18th Century. The Honor System-Based Post Office is Established

“You’ve got mail!”

—America Online

“Baltimore … London … Carlsbad!”

After landing on Floreana Island, located along the southwest limits of the islands, we gather around to hear the destinations of dozens of postcards called out. The postcards had been left behind in a barrel found a little ways up from the beach. The missives have been left by visitors for the tourists that follow to hand deliver to their intended recipients. What may seem like a chore is actually a time-honored tradition that goes back hundreds of years.

When visits from pirates and buccaneers tapered off, they were soon replaced by whalers and sailors who found the islands to be a convenient place to stop and refuel over the course of their long voyages.

But with no traditional postal service, the sailors decided to make do with nothing but a wooden barrel and faith in their fellow seafarers.

Sailors would stop in what became known as Post Office Bay and leave their missives in the barrel with their intended destination. Others who were on the return parts of their voyages would go through the letters and deliver whatever mail they could upon their arrival.

Now, the Galápagos’ population is served by a standard postal service, though it’s jokingly said that you’re likely to get faster delivery by dropping your mail off in the old-fashioned barrel. And given the fact that the postcard I sent via barrel showed up in Los Angeles after just two weeks, I’m inclined to believe it.

1819. Whaleship Essex Sets All of Floreana on Fire

“The roof, the roof, the roof is on fire!”

—Rock Master Scott & the Dynamic Three

After climbing up the Pinnacle Rock Overlook up on Bartolomé Island, I’m able to look across the small strait that separates us from the lava flow on Santiago. Scanning the blue waters and extreme landscape, it’s easy to be overwhelmed with the desire to go beyond the marked trail and explore in earnest. Only doing so is verboten. In addition to macro-level laws, like the one that established 15,000 square miles of Galapagos waters as a marine sanctuary, there are strict laws about where tourists are and aren’t able to go. Going off-road is simply not on the menu. In fact, the local and Ecuadorian governments have set up some of the strictest conservation laws on the books. Which is understandable when you consider previous visitors would do things like set entire islands on fire.

Leaving an island consumed by fire would’ve been the worst disaster to mark most 19th-century whaling voyages. But when the whaleship Essex left Floreana, after leaving the place engulfed in flames, the ship’s final and ill-fated voyage find it sailing off into the maw of one of the worst nautical tragedies on record—an encounter that would become famous for inspiring Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick.

After discovering the Essex’s intended whaling grounds had been disappointingly reduced, it was decided to make for the far-flung “offshore ground.” But before setting out into the South Pacific proper, the ship stopped to resupply in the Galápagos. There, the Essex carried on the tradition of taking giant tortoises (300 in fact) on board in order to resupply their food stores.

While on the island of Floreana the ship’s helmsman, Thomas Chappel, decided to set a fire because, naturally, he thought it’d be pretty funny. However, the prank fire quickly got out of control, forcing the crew to cut their giant tortoise hunt short so that they could flee the spreading inferno. After sailing for a full day, the fire could still be seen on the horizon.

It’s believed that the devastating fire was largely responsible for the near extinction of the Floreana giant tortoise and the Floreana mockingbird.

1835. Darwin is Actually the Worst Tourist

“A man who dares to waste one hour of time has not discovered the value of life.”

—Charles Darwin, a man who rode giant tortoises

A full-throated grunt goes up from somewhere in the distance.

With its plentiful mud, shade, and vegetation, the Wild Tortoise Reserve on Santa Cruz is an ideal refuge for the Galápagos’ iconic gentle giants to get in some quality “me” time. And while most of their compatriots are pretty shy (they’ll quickly retreat into their shells when they notice a human in front of them), one pair, in particular, had a more exhibitionary disposition.

We make our way across the reserve, following the steady intervals of guttural, short groans.

Stumbling across a pair of gigantic reptiles locked in an amorous embrace is not something I’d ever envisioned. I don’t know how you’re supposed to react (“Oh! Pardon me good sir, madame!”) but I’m pretty sure you’re not supposed to stand rooted to the spot openly staring which is exactly what I ended up doing. And while gawking at two giant tortoises mating for a solid five minutes (which is, to be fair, a mere blip in what are typically four-hour sessions) may seem odd, it makes Charles Darwin’s famed visit look utterly restrained by comparison.

We all know Charles Darwin as the 19th-century naturalist whose famous contributions to the science of evolution solidified his image as a Very Serious Man. But if Darwin were to visit the Galápagos in the present day, he would’ve been run out on a rail (after being slapped with a fine, if not jail time). As it turns out, when he wasn’t sketching finches, he was getting hands-on with the local wildlife.

According to his writings in The Voyage of the Beagle, the famed naturalist wasn’t above playing at horsey with the giant tortoises.

“I frequently got on their backs,” wrote Darwin. “And then giving a few raps on the hinder part of their shells, they would rise up and walk away;—but I found it very difficult to keep my balance.”

When he wasn’t on one of his giant-shelled steeds, Darwin was also prolific at antagonizing the marine and land iguanas. And while there might be a scientific defense for dissecting a few of the unfamiliar reptiles, it’s difficult to see what part of the scientific method condones throwing an iguana, in Darwin’s words, “several times as far as I could.”

He writes about watching one land iguana burrow in the ground for a while before Darwin, apparently taking on the temperament of a toddler set on pestering the family dog, decided to escalate things. “I then walked up and pulled it by the tail, at this it was greatly astonished, and soon shuffled up to see what was the matter; and then stared me in the face, as much as to say, ‘What made you pull my tail?’”

Sure, his status as a scientific figure is unquestionable. But as a tourist, Darwin was kind of a jerk.

1929. Satan Comes to Eden

“I’m not here to make friends.”

—Kelly Wiglesworth, “Survivor” season one runner-up

It’s night on the Grace. The ghostly outlines of Galápagos sharks lazily swim in and out of the corona of light cast by the yacht. A dome of impossibly numbered, impossibly bright stars arcs against the pitch black sky. I, along with the rest of the passengers, have gathered on the deck to hear Dolores Diez, co-founder of Quasar Expeditions, regale us with a true story of the Galápagos so unusual it makes every fantastical campfire story feel drab by comparison.

By 1929, a small but permanent population had been established in the Galápagos, most of which was concentrated on the islands of Santa Cruz and San Cristóbal. That, however, wasn’t isolated enough for two German ex-pat families who decided to make the island of Floreana their new home. The two households had their minor differences but these neighborly squabbles were nothing compared to what was to come.

Floreana’s most notorious resident arrived one day riding a donkey, rifle in hand, and flanked by “two gentlemen in waiting.” She introduced herself as the Baroness Eloise von Wagner of Paris, by way of Vienna. And she was very quick to let the everyone know that this was her island now and proceeded to treat the two other households as lowly subjects.

The Baroness’ “reign” over Floreana was fraught, to say the least. Right off the bat she set up camp in one family’s orange grove and claimed the precious fresh water spring for herself, unilaterally decided that the small island should be the site for a luxury resort, and allegedly attacked a misfortunate pair of Norwegians that had come from Santa Cruz to hunt for beef.

But though she made for a contentious neighbor, the Baroness’ strident and larger than life personality gave her an effective, if eccentric, charm. An American scientific research vessel called the Valero, which would intermittently visit Floreana, even made a short film starring the Baroness, in which she portrayed a fearsome pirate queen. When tales of the dreaded “Empress of the Galápagos” and “her several husbands” hit Europe, she became a newspaper sensation.

But the primetime soap opera worthy drama culminated in a series of tragedies that have remained a mystery to this day.

Of her two lovers, the Baroness had come to prefer Robert Philippson over Rudolph Lorenz which, combined with a punishing drought and dwindling supplies, had ratcheted up the tension at the Hacienda Paradiso. Then one day, Dore Strauch, according to her journal, heard the terrifying, unmistakable scream of a woman. At first, she ascribed it to a delirium brought on by the unforgiving heat. But not long after that Margret Wittmer and Lorenz appeared. Wittmer, in a story that sounded rehearsed to Strauch, said that the Baroness had visited the Wittmer homestead to declare that a yacht belonging to friends of hers had appeared, and that she and Philippson would be going with them to Tahiti.

Strauch was unconvinced that any Tahitian getaway had taken place. But, fearing what would happen to her if Lorenz was a murderer, said nothing of her suspicions.

If Lorenz had anything to do with the disappearance of the Baroness and Philippson, he would take it to his grave. Desperate to leave the Galápagos, he sought passage on a fishing boat, offering the captain an extra 50 sucres if they left at once. The boat, however, would never reach the mainland. It was found two days later floating off the coast of San Cristóbal, empty.

Later, Captain G. Allan Hancock of the scientific vessel Velero, discovered two bodies mummified by the arid environment on the waterless Marchena, one of the northernmost islands. Hancock, who was well-acquainted with Floreana’s colorful inhabitants, immediately recognized the blond-haired, knitted sweater-clad remains of Lorenz.

The Baroness and Philippson were never found. The truth about what really happened on Floreana has yet to come to light.

2006. The Judas Goat

“Yea, mine own familiar friend, in whom I trusted, which did eat of my bread, hath lifted up his heel against me.”

—Psalms 41:9

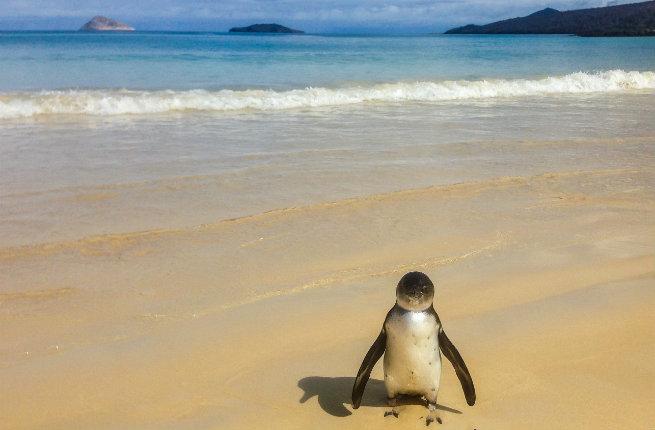

There are many endemic birds you’re likely to see when visiting the Galápagos. The Galápagos mockingbird, red-throated frigate birds, and of course the famous blue-footed boobies. If you go at the right time you might even catch sight of an albatross, massive wingspan and all. I stopped understanding how I could be in the real world the moment a baby Galápagos penguin waddled up onto a beach on Floreana, cheerily posing for photos.

What you’re not likely to see, however, is the mangrove finch.

The mangrove finch (one of “Darwin’s finches”) is critically endangered due to predators—rats and parasitic flies—that were introduced to the islands. Conservationists have worked to stave off extinction by “managing” the populations of invasive species. The tactic of removing introduced species in favor of endemic ones has been utilized before—but perhaps never as dramatically when it came to the hundreds of thousands of goats that had come to dominate the islands.

With an ecosystem as delicate and unique as the Galápagos archipelago’s, any introduced species carries the potential to wreak havoc. And perhaps one of the most damaging of the islands’ newcomers was the feral goat.

The goat first appeared hundreds of years ago when they were brought by sailors and pirates. In the intervening years, the goats, not known for discerning or restrained sensibilities when it comes to food, destroyed so much of the local vegetation that they were directly endangering the Galápagos’ endemic fauna—including giant tortoises—who couldn’t get enough to eat because the goats were hogging it all.

The choice, unfortunately, came down to garden variety goats or entire populations of species that can only be found in one place on the entire planet.

The goats lost.

Taking their cue from a similar tactic that had proven effective in New Zealand, the Galápagos National Park and the Charles Darwin Foundation launched the Judas Goat project. The premise was simple. Take a female goat, sterilize her, equip her with a tracking device, and slather her in hormones so that she was rendered irresistible to the other goats. Then wait until the Judas Goat led hunters to their ill-fated brethren and then, well, finish the job.

While some of the goats were killed by hunters with simple rifles who traveled by ground, there was another, more flashy tactic employed. Specialized hunters from New Zealand used aerial techniques to hunt down the goats. “Aerial techniques” being the less dramatic way to say “gunning down goats with semi-automatic weapons from a helicopter in hot pursuit.”

All in all, the project was carried out over the course of six years and cost $6 million, resulting in the eradication of 80,000 goats on Santiago Island alone. And while it may seem bizarre—it may seem cruel—but project Judas Goat was ultimately successful. The vegetation was able to regrow and the giant tortoise population is slowly but steadily increasing.

So much for natural selection.

But then, it’s understandable how these decisions are reached. The morning of my final day is spent on the panga, quietly navigating a mangrove tree estuary on Santa Cruz, the large island that can be found at the heart of the archipelago. The ancient trees loll in the still water, the sun catches the cresting shells of turtles, the outline of juvenile hammerheads weave in and out of sight. The only reason any of this has survived—whether it’s been the threat of volcanoes, fires, pirates, goats, and Baronesses—is because of the difficult decisions and hard work of the people preserving this world unto itself.

No matter how you see the Galápagos—beautiful or stark, paradise or purgatory—it is a glimpse into the world perhaps as it should be. Pristine and unknowable, its animals fearless because humanity has given them no reason to be afraid. A reminder that the world still has the capacity to surprise and transform us.