As the city reopens, Rio de Janeiro is trying to reclaim its beat.

Life is slowly resuming in Rio de Janeiro as it enters its fifth stage of easing lockdown measures. Residents can now enjoy group beach footvolley sessions before taking a dip in the sea; restaurants, bars, and cafes are open at 50% capacity and the city’s beloved gyms and retail outlets have reopened. International borders are now partially open to foreign visitors.

Despite Brazil’s growing cases (3.7 million as of August 25) and its status as one of the worst-hit nations, concerns about coronavirus in Rio is waning, with many maintaining that the worst is over. “Low demand for intensive care, hospital beds, and the stabilized death toll show us that we had the darkest peak in May before gradually dropping to current levels,” said Rio’s Mayor Marcelo Crivella earlier last month.

After the virus ravaged the city, the disease is now migrating inland into small rural towns without basic healthcare systems. While health authorities argue that lockdown might be necessary in the country’s interior, many here in Rio de Janeiro are desperate to save the economy from the catastrophic effects of lockdown.

Due to the extreme level of inequality that permeates the city, the local experience of the pandemic has been very divided. Where lockdown might be possible for the upper-middle class who can work from home and self-isolate in comfortable living environments, isolation was never an option for many in poorer communities due to inadequate sanitation and crowded housing. The majority of Rio’s favela (low-income neighborhood) residents are also informal workers who would starve if they did not go out to work. While the city’s rich might be “tired” of lockdown, the city’s poor are “hungry.”

Recommended Fodor’s Video

Fodor’s spoke to a range of professionals from varied social classes about their feelings regarding living in one of the hardest-hit countries in the pandemic. What I found was an unsettling mixture of optimism, alarm, and anger but a unanimous eagerness for the city to return to some level of normality.

The Consultant and Teacher

Rodrigo is a consultant and teacher living in Botafogo and looks at the situation through an intellectual and political lens. For him, the lack of coordination between different government entities has been the country’s biggest issue.

“The federal, state, and municipal levels have been butting heads since the start of the pandemic. The federal government, who has the capacity to distribute funds and resources, took a chance on denying there was ever a problem and left those already struggling to fend for themselves,” Rodrigo said.

“There’s also the issue with Rio’s state governor, Wilson Witzel. His aids have already been caught in major corruption scandals which have contributed to a public mistrust towards authorities.”

Rodrigo points to the government, especially President Jair Bolsonaro, as the root cause of public hostility towards lockdown measures. “Bolsonaro has continuously said that the disease is not serious and has encouraged people to keep working rather than staying home. The structural cause is that a huge percentage of the Brazilian population lives paycheck to paycheck. Since the government has [willingly] failed to provide adequate support for business owners, and the monthly payments for people to stay at home are not enough, people have been forced to find a way to keep working.”

The IT Manager

Not every Brazilian however, shares Rodrigo’s skepticism towards Bolsonaro. Andre is an IT Manager and Bolsonaro supporter living in the wealthy Copacabana neighborhood. From Andre’s perspective, public health should always be linked to the economy. He believes that Bolsonaro has always looked at the pandemic from a manager’s point of view.

“Bolsonaro is right in questioning lockdown, there is no empirical evidence that it’s successful. I believe in vertical isolation [quarantine only for at-risk groups], all hygiene and preventive efforts.”

Andre also feels that the country’s high-death toll does not paint the whole reality: “The only metric that should be used to calculate the coronavirus death count is death per million. It’s absurd to compare such a large country like Brazil [with a population of over 209 million] to a smaller country like France.” According to Johns Hopkins, Brazil has the tenth-highest rate of death per population.

He adds, “Brazil is the country that has the most recovered coronavirus people worldwide.” Almost 3 million have been reported to have recovered in Brazil.

The Restaurant Manager

Given the number of people who have already recovered from the disease, restaurant manager Flavio Dantes from La Carioca in the Leblon district is hopeful for the future.

“I’m confident people will return. Locals love to socialize and have fun, this is the Rio lifestyle…Because of our socio-economic situation, the city never really stuck to a strict lockdown, compared to other countries. I believe that the city will soon have a very high level of immunity and the risk of a second wave will be much lower. Brazil will be one of the safest countries in the not too distant future because the population will be completely immune.”

It’s a common opinion held by many Brazilians. At the cost of many deaths, and with secret parties widespread among the youth, many are hoping to achieve herd immunity. Everyone is in agreement that at-risk groups should quarantine, but many believe that the more young and healthy that catch the disease the better.

As a city that lives almost entirely outdoors, Flavio also cites the psychological strain that lockdown has had on many Rio residents: “There is currently a very large mental health crisis because the local population does not know how to stay indoors.”

The Lifeguard

Pedro is a lifeguard at Arpoador beach who has been fortunate enough to keep working throughout the pandemic. He has a very balanced picture of the public’s response to lockdown and the city’s phased reopening.

“One of the first things the city mayor did was issue a ban on visiting the beaches. Ever since the beaches slowly began to reopen to individual and group sports, the maritime police have found it very difficult to control locals who are choosing to sunbathe and congregate in groups despite this being prohibited. With such a large population, how do you monitor an entire beach?”

He adds, “People have been rebelling. The public is disillusioned from Rio de Janeiro’s politics and many believe that the pandemic is being exaggerated by the media to steal public funds.”

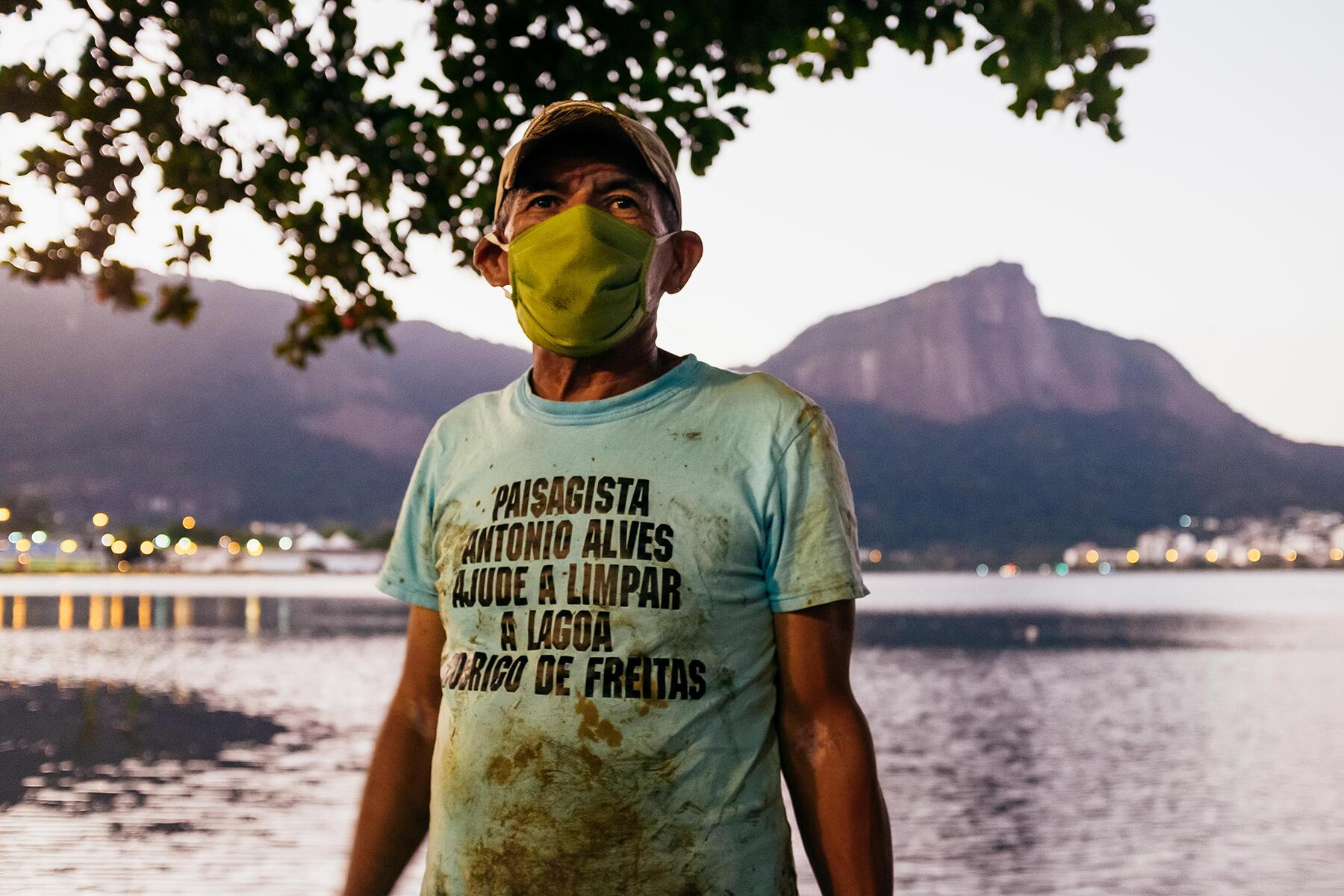

The Informal Worker

Wellington is a vendor at a fruit and vegetable market in Ipanema who lives in Caxia, a Rio suburb. He is one of Brazil’s informal workers who make up around 40% of the country’s workforce and has needed to continue working during the pandemic to put food on the table for his family.

“My work is very difficult right now because of the pandemic. I think the situation will get better next year. I have also been searching for construction work near my house to try to make ends meet. I became very depressed at home so I’m happy now to be back working on the streets.”

All sectors are relieved to be back in business to some degree but with cautious optimism and can only hope that now the city is starting to open up, the situation will improve in the coming weeks and months.