Some people may guess that the nation’s oldest federal monuments are in Washington, D.C. That makes sense. But you’re wrong if you think they’re on the National Mall or on Capitol Hill. And think again if you’re envisioning grand classical pantheons or even towering marble columns.

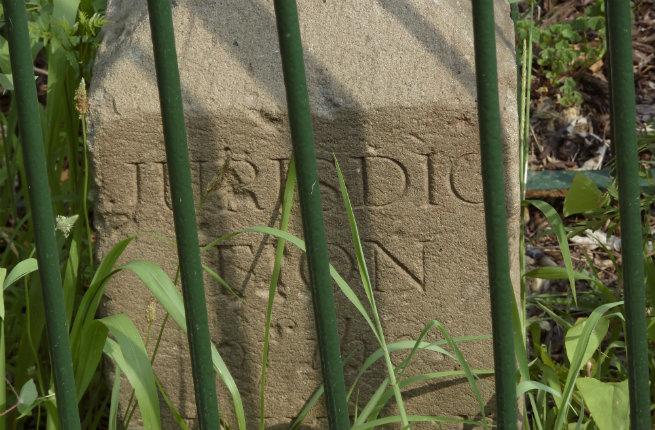

What would you say if you learned the oldest federal monuments are actually little sandstone markers standing 2 feet tall and a foot square that resemble George Washington’s false choppers? And that they’re tucked away in people’s backyards and under a lighthouse and amid brambles along the Potomac River and even right in front of a Metro stop?

And yet there they are, 40 of them, sprinkled around Washington, D.C., protected by Victorian iron fences. Few people realize they’re even there. Or worse—they’ve seen them but haven’t given them a second glance. But they may very well be the most important monuments in the nation’s capital.

So what are these “boundary stones?” In short, they are the city’s earliest geographical markers.

“Without the boundary stones, there wouldn’t be a Washington, D.C.,” says Stephen Powers, co-chair of the Nation’s Capital Boundary Stones Committee. “George Washington was given 10 years to set up the city here. If he failed, it would go to Philly.”

Recommended Fodor’s Video

So the first order of business for the newly inaugurated President was to establish the capital city’s 100-square-mile site. “Before building the White House. Before building the Capitol,” Powers says. “He was under the gun.”

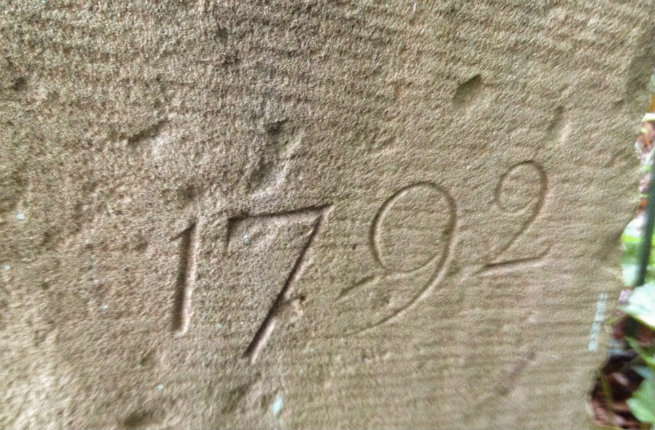

A surveying party led by Major Andrew Ellicott set out in 1791, methodically clearing the land and charting a 10-by-10-mile diamond shape encompassing the “Federal Territory.” They planted stone markers a mile apart along each border, with larger stones marking the north, south, east, and west corners. Within a year and a half, Washington’s parameters officially had been defined, and Washington’s choice location for his capital city was saved. All he had to do next was build the White House and Capitol.

A lot has changed since the boundary stones were first planted, and perhaps the coolest thing about them is the chance they offer to experience Washington’s different neighborhoods—from historic and gritty Anacostia to tiny Chevy Chase, from Northeast’s working-class neighborhoods to Northwest Washington’s enclave of the political elite.

A tour of all 40 requires knocking on people’s doors, climbing through bushes, requesting permission to enter a water treatment plant, and following a trail map through a historic cemetery. And with 40 miles of perimeter to cover (actually more, since few stones can be accessed in a straight line), it may take days or weeks to visit them all. There are those who bike to find them (or go on the annual Boundary Stones Bike Ride, typically slated in October). Others hike. Powers offers a guided tour in May (contact him through the boundary stones website). However you do it, it’s a true historical treasure hunt, and a fabulous way to visit out-of-the-way corners of D.C., far from its sparkling corridors of power.

Here’s a quadrant-by-quadrant primer to get you started:

Southwest Quadrant

President Washington wanted to make sure that Alexandria, one of the country’s busiest ports, would be within the 100-square-mile confines of the new capital. As such, Benjamin Banneker, a prominent surveyor and astronomer, lay on his back for six nights to study the stars and calculate that the southernmost point within those parameters was Jones Point. And that’s where the surveying party began their work, moving clockwise through the Virginia territory from Jones Point.

Wait, back up. Virginia? That’s not in Washington, D.C.! Well, actually Alexandria County was, originally. When the surveyors first assessed the land, they took a chunk out of Maryland and a chunk out of Virginia. Then Virginia wanted its land back. A separation movement blossomed, culminating in the 1847 retrocession of Alexandria County (which today is Alexandria city and Arlington County), shrinking the district by a third. So the current lands comprising today’s Washington, D.C., are actually former Maryland territory.

To see that first boundary stone at Jones Point, head to Alexandria, right along the Potomac. When a lighthouse was built on the spot in the mid-1800s, the stone was built into the seawall—so to find it, you have to peer into the dark recess.

From there, most of Southwest’s stones are in plain view—along a street near the Masonic Temple, in the parking lot of a church, in a park named for Benjamin Banneker. You’ll travel through some pretty neighborhoods, as well as a congested shopping corridor, ending at Andrew Ellicott Park in Falls Church, Virginia.

Note: Each one is named by its quadrant and position from the cornerstone; the first stone you come to after Jones Point, for example, is called SW1, meaning it lies in the southwest quadrant and is 1 mile from the south cornerstone.

Northwest Quadrant

Continuing clockwise through the Virginia territory, the northwest quadrant covers north Arlington then crosses over the Potomac River into northwest D.C. These are grand neighborhoods, with large brick houses and ancient trees—the domain of Washington’s power elite. Here, a couple markers hide away in people’s backyards (NW2, NW3). Go ahead and knock on the doors—someone does at least once a month, say the easygoing residents. And several are firmly planted in front yards, including NW8, hidden by a bush (it’s illegal to remove them, even if they don’t match your landscaping).

One of the most difficult to access stones—NW4—is here too, on the grounds of the Dalecarlia Water Treatment Plant, north of Georgetown. You must contact the facility ahead of time to gain permission, then be accompanied to the stone. And don’t forget your I.D. to get through the gate! But the employees are happy to accommodate you—they know exactly where the marker is, meaning that once you’re inside you don’t scramble trying to find it because you’re guided straight to the spot (and can ask questions and get some insight along the way).

Northeast Quadrant

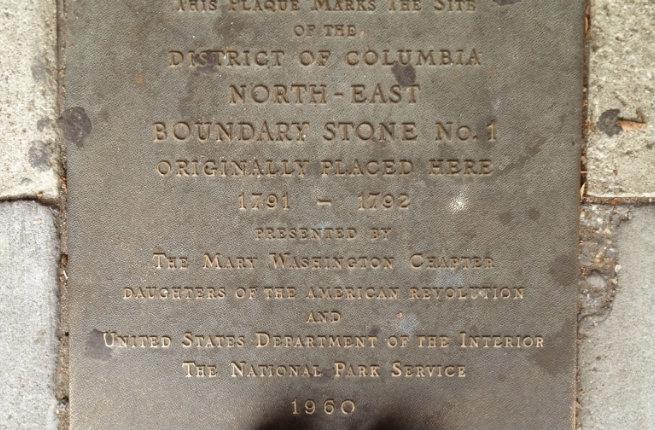

From the northernmost point of D.C.’s diamond shape, the northeast quadrant encompasses working-class, traditionally African American neighborhoods. The most interesting stone here may be NE7, located within the historic Fort Lincoln Cemetery, which integrates a Civil War fort. NE1, tucked away in a row of Ethiopian shops near Silver Spring, was accidentally bulldozed in 1952; today a plaque memorializes it—several stones have gone missing through the years, though they are slowly being replaced (in fact, SE4 and SE8 were replaced in 2016).

Southeast Quadrant

Continuing southeast back to the original south marker at Jones Point, Southeast contains D.C.’s historic Anacostia neighborhood, once home to civil rights leader Frederick Douglass. A string of stones on properties along Southern Avenue provides one of the best stretches to easily spot a bunch. And SE7 sits at a busy intersection where locals play chess, sell water bottles, and welcome treasure hunters with a curious glance, providing a glimpse into D.C. daily life far from the Hill’s political shenanigans.

But this quadrant also contains the most difficult marker to find. SE9 sits above the marshy banks of the Potomac River, with no trails to access it. “The easiest way to get to it is from I-295,” Powers says. “Look for the Maryland/D.C. sign, then scramble through a little hole in the fence. But you really need to know where it is.” You can also access it via Oxon Cove, which requires clambering beneath the highway and over sharp rocks. No doubt, in this natural state, you get a sense of what our forefathers were up against when they set out to survey the original boundaries of our great capital. To think that the stones they laid out remain to this day is a precious reminder of the hopes and dreams of a fledgling nation—and all that it has become today.

Insider Tip: Check out boundarystones.org, which has maps, detailed directions on how to find each stone, as well as lots of background info.

PLAN YOUR TRIP: Visit Fodor's Guide to Washington, D.C.