Houston's National Museum of Funeral History puts the fun back into funeral.

The readers of the Houston Press certainly think the National Museum of Funeral History is fun—after all, they named it the best museum in 2021.

“Death has been in our faces more than anything this past year,” says Genevieve Keeney, a mortician, and the president of Houston’s National Museum of Funeral History. “You can evade taxes; you can’t escape death. The Grim Reaper will definitely get you!” Her witty remarks, easy smile, and upbeat attitude don’t fit the picture of a mortician—meaning both a funeral director and embalmer.

“A lot of people are expecting to see something morbid and a little bit scary,” Keeney says. What they see is the largest museum in the nation devoted to the history, traditions, and rituals of caring for the dead. “There’s something for everyone. If you like cars, you’ll love the hearses. If you love history, you’re going to love this museum. People lose track of time here.”

The museum not only takes you through the history of burials and funerals from pharaohs, popes, presidents, and celebrities, but shows off quirky coffins, high gloss hearses, and so many options for your ashes that you’ll be wishing you had more than one life to lead.

Recommended Fodor’s Video

It all begins with the Presidential Funeral Gallery and memorials to George H.W. and Barbara Bush. Bob Boetticher, a mortician and the museum’s chairman, is the man who plans presidential funerals. His contributions to the museum have made the presidential exhibits particularly meaningful.

The museum contains artifacts from all the deceased presidents, beginning with George Washington’s $99.25 funeral bill from 1800. Some memorabilia are familiar, like the iconic photos of John F. Kennedy Jr. saluting his father’s coffin and a despondent Nancy Reagan draped over her husband’s casket.

Some displays hold one-of-a-kind artifacts you’d never expect to see, including strands of President Lincoln’s hair. Dr. Charles Leale, the first physician to tend to the president, cut Lincoln’s hair to better see his wound. Leale gave the lock to Mary Lincoln. Saving a loved one’s hair for mourning art or jewelry was a Victorian ritual intended to keep the deceased close.

Lincoln was the first president to be embalmed. Preservation allowed people to pay their respects to Lincoln as he passed through towns on his funeral train. Emotionally unable to accompany her husband, Mary had their son Willie exhumed. He had died three years earlier from typhoid fever. A model of the horse-drawn hearse that carried the coffins of both father and son is on display. Pointing to the model, Keeney says, “The larger the plumes, the greater the socioeconomic status. If a hearse with very large plumes passed by, everyone would know that was a very important person.”

More modest black feather plumes top a horse-drawn hearse from 1826, one of the oldest hearses in the museum’s collection. The fleet also includes a hand-carved 1921 Rock Falls hearse and a Japanese ceremonial hearse. The museum’s newest hearse carried Presidents Gerald R. Ford and Ronald Reagan. Flags replaced plumes and it’s so shiny you can see your reflection in it.

“The mission of the National Museum of Funeral History is to educate visitors on the customs, traditions, and rituals in caring for our dead, not only here in America but worldwide,” Keeney says. An exhibit called Celebrating the Lives and Deaths of the Popes does just that. It explains the steps taken after a pope dies, from destroying his fisherman’s ring that was used to seal documents to interpreting the smoke signals that announce the election of a new pope.

The museum pays tribute to those who have entertained us or touched our lives in Thanks for the Memories. The exhibit honors celebrities, sports figures, astronauts, and Arch West, the Frito-Lay marketing director credited with inventing Doritos. Marilyn Monroe’s original crypt façade is steps away from “The 27 Club” of celebrities who died at age 27. The club has far too many members, including Janis Joplin, Amy Winehouse, and Jim Morrison. Morrison’s line in the song, Five to One is right—“no one here gets out alive.”

Benjamin Franklin had his own version: “In this world, nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes.” Everyone faces the same fate. But caring for the dead has changed since Franklin’s time and is showcased in the embalming and cremation exhibits. Although embalming began in Ancient Egypt, it wasn’t used in America until the Civil War. It allowed deceased soldiers to be returned to their families.

During this time, funerals took place at home. The 19th Century Mourning exhibit shows a wake in the home’s parlor–the ritual of waiting three days before burial in case the “deceased” awakened. Along with mourning clothing displays of the big black dress variety, mourning hair art hangs on the parlor’s wall.

Mourning art will probably give you the creeps. “Everyone has something that gives them the heebie-jeebies,” Keeney says. “The big wreath is a generational hair wreath, meant to be passed down.” Keeney says this tradition is even making a comeback.

The museum’s newest exhibit features postmortem photographs from the same era. The photographs show the deceased, mostly children, in their Sunday best, propped up by a mom or siblings for a family portrait. Like mourning hair art and jewelry, the images were a way to keep the loved one close.

An unused casket is on display: Grieving parents ordered a three-person coffin to be forever closed after their child’s death. They planned but never executed their murder/suicide. The museum’s other unique coffins to view are for single occupants, including the hand-hewn chicken-, leopard-, and outboard motor-shaped coffins from Ghana; and a coffin inlaid with $643 that proves you can take it with you.

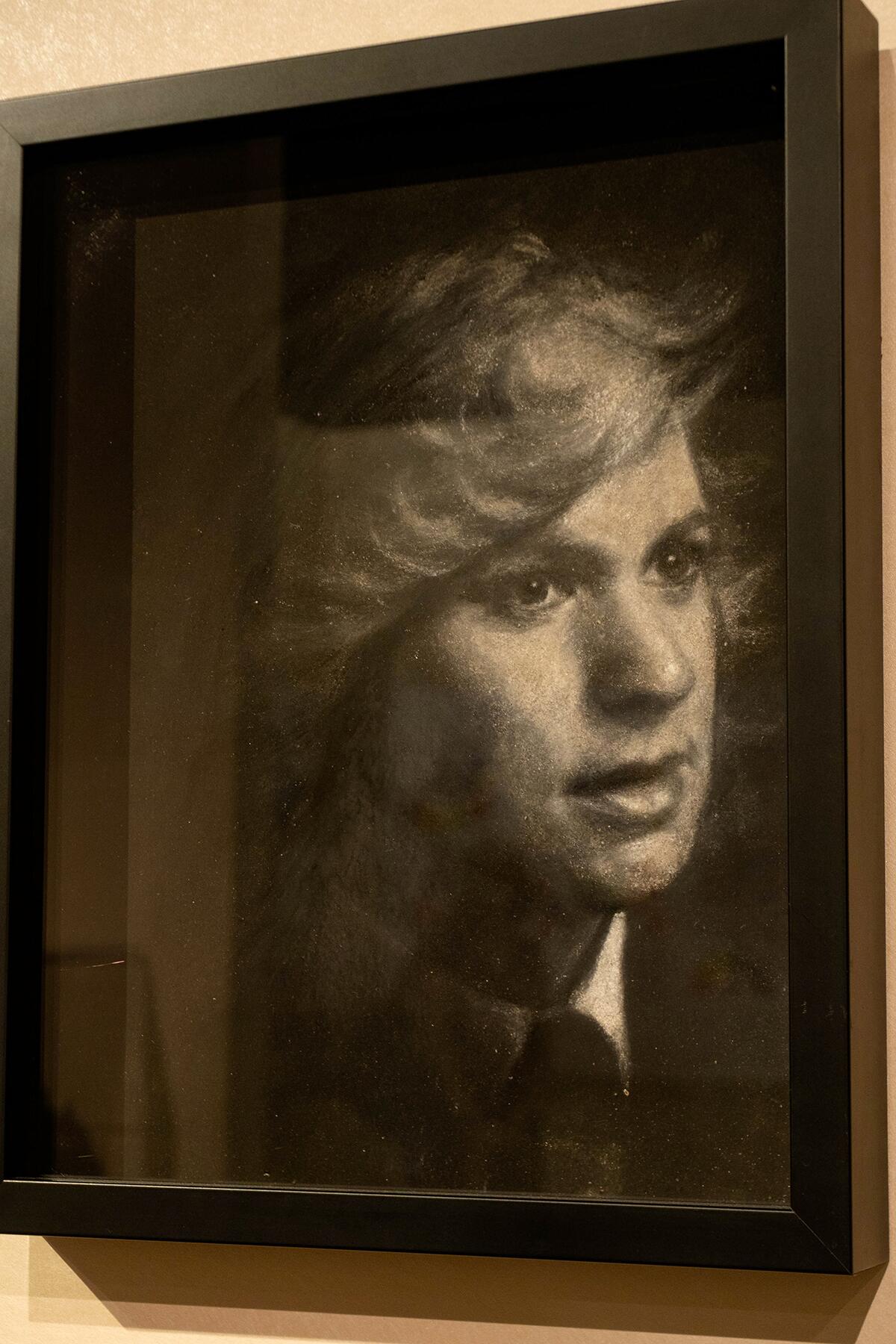

The recently curated History of Cremation exhibit is Keeney’s favorite. Along with a replica of the first crematorium in the U.S., the display showcases everything that can be done with ashes—from saving them in an urn to compressing them into diamonds. “In doing the history of cremation exhibit, I learned all these amazing things you can do with cremated remains. I’m glad we had my sister cremated because I brought her back into my life. That portrait is my sister. Those are her ashes,” Keeney says as she points to artist Heide Hatry’s rendering. “I have her close again. To me, that’s what cremation is about.”

Death is our common denominator. “Live every day to its fullest. You are never promised tomorrow,” Keeney reflects. The joyous video in the Jazz Funeral exhibit and the museum’s motto, “Any day above ground is a good one,” echo that sentiment.