Like every major national park, it’s more than its natural wonders.

T

here is nature’s magic happening at Hot Springs National Park. Rain that fell when the Egyptian pyramids were built has slowly, over 4,000 years, fallen through the earth and, on its way down, warmed to 143 degrees Fahrenheit, absorbing minerals from ancient rocks that formed from an early seabed. Near a faultline in the Ouachita Mountains, the water vents in 47 thermal springs have brought humans seeking healing, solace, and restoration to what is now central Arkansas for more than 3,000 years.

Hot Springs National Park officially reopened earlier this month for the first time since the outbreak of COVID-19 and has also just marked its centennial year. Like every major national park, it’s more than its natural wonders—its story has layers, shaped by westward expansion, a new industry of wellness, and the Jim Crow era. Human history and geologic change are intertwined, and the centennial anniversary prompts a look at how the park realizes the NPS mission to coalesce nature, culture, and history to tell a complex story.

A mythic gangster-era had a hand in shaping downtown Hot Springs, when Al Capone, Bugsy Siegel, and many others followed Owen Madden (former owner of the Cotton Club and the Stork Club) to the city in the 1930s. Downtown Hot Springs is now reminiscent of an old Western frontier town in the midst of a modern, creative renaissance, with new breweries and hotels in revitalized, turn-of-the-century bathhouses, enveloped by sweeping tableaus of the Ouachita Mountains. The Ouachitas predate the dinosaurs. They formed when colliding tectonic plates forced an ancient seafloor upward and have worn away over time to create picturesque mountain valleys and a vast, forested wilderness.

Recommended Fodor’s Video

The park’s museum curator Tom Hill notes, “People have been coming to Hot Springs to get what they need out of the ground, whether it’s rock or water, for thousands of years, not hundreds of years.” The park’s tribal partners are from the Shawnee, Osage, and the Caddo and Quapaw nations, the latter two of whom ceded massive acreages to the U.S. government in the early 1820s. Evidence of early quarrying sites is discernible throughout the park, where Indigenous communities mined for Arkansas Novaculite, the same rock that enriches the water, for making tools and weapons, preparing hides, stripping bark, and for trade, Hill explains.

People began arriving from the east in greater numbers following the Hunter-Dunbar expedition’s documentation of the springs in 1803. Local congressional representative Ambrose Sevier sought federal protection, hoping to avoid haphazard land claims and monopolies. The designation of Hot Springs Reservation in 1832 was the very first federal designation to protect a natural resource, 40 years before Yellowstone became the world’s first national park.

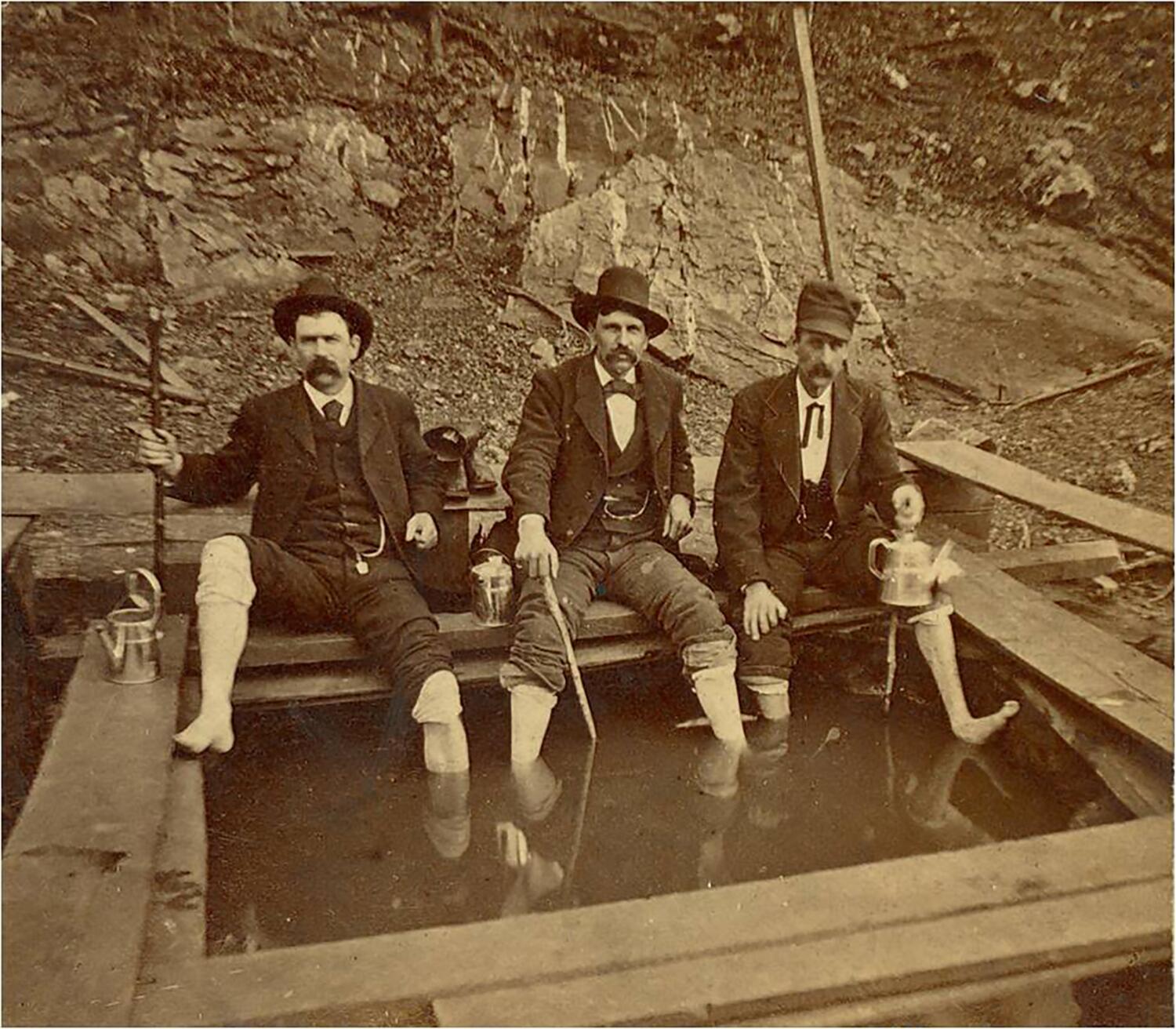

In the 19th century, Civil War injuries, exhaustion from manual labor on farms and settlements, and illnesses like syphilis and rheumatism drew thousands to the area, a time when not every home had a bathtub—just soaking in Hot Springs Creek offered a reprieve from the demands of day-to-day survival. Thousands have left written testimony that the water saved their lives, including former Civil War Colonel Samuel Fordyce, who built an opulent turn-of-the-century bathhouse that is now the park’s Visitors Center and museum.

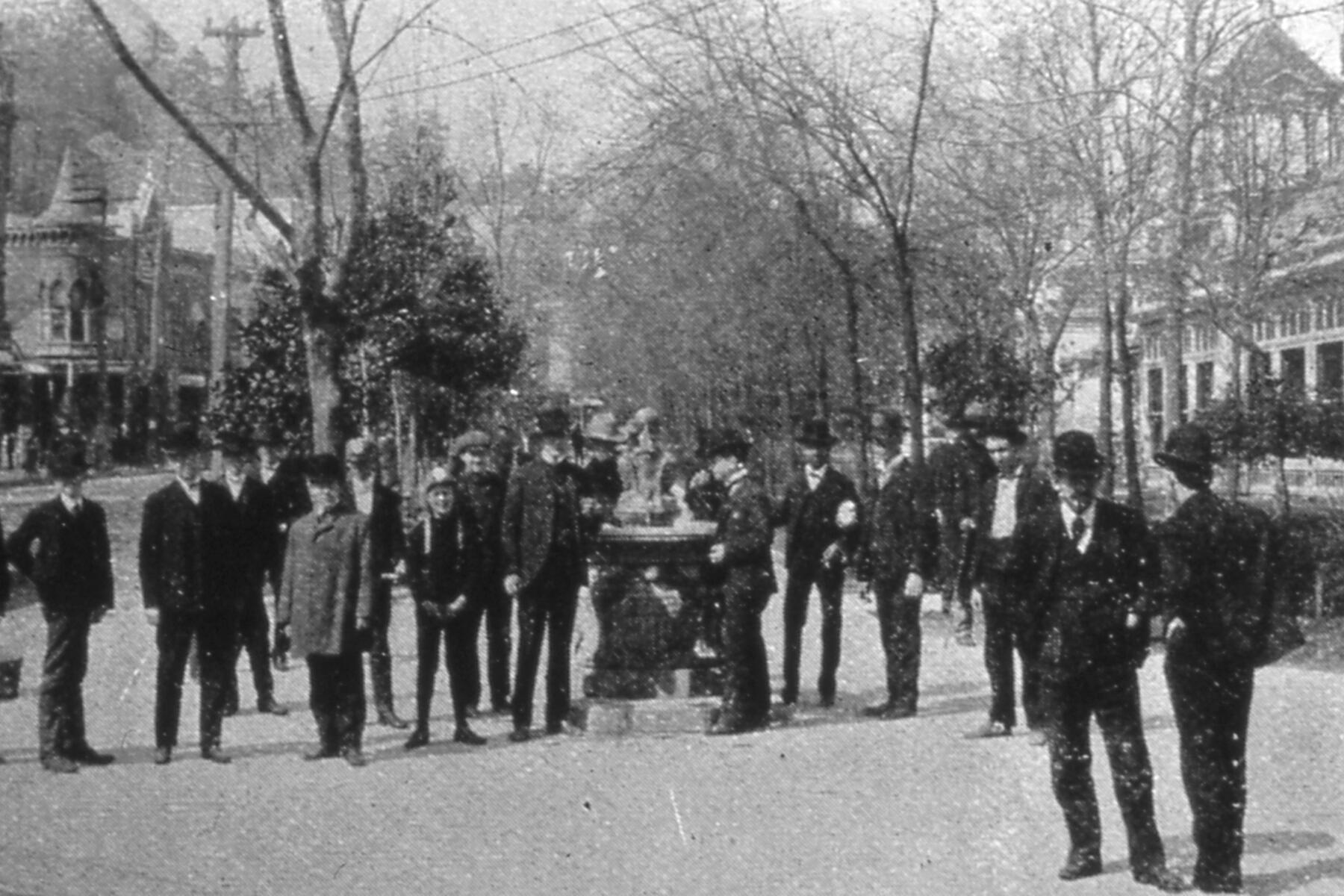

In 1892, the government leased land to private entrepreneurs who opened bathhouses ranging from posh to practical. Fordyce’s ornate facility fully embraced the Industrial Age, with treatments like Zander mechanotherapy, which moved the body through a series of simulations, including cycling, horseback riding, and boxing. Spring water coursed through jets and hoses aimed at the spinal column to treat conditions from depression to stomach ailments to arthritis, and there were steamed in metal cabinets where only the head was not enclosed. Attendants applied hot packs and bathers soaked in enamel tubs and immersion tanks and paid extra for special treatments like mud wraps and private soaks. A bathhouse visit would often include rest in sitting rooms and on sun porches, and “taking the mountain air” along early hiking trails. During the heyday of bathing, before bathhouses began shuttering in the 1960s, Bathhouse Row might have run the reservoirs dry for very brief periods.

“A lot of it is living just beneath the surface, to be extrapolated and expanded upon,” observes ranger Ashley Waymouth. “And given that the NPS was only five years old and we were the 18th national park to be named, we get to be part of this collective vision for American stories,” she continues.

Many still journey to Hot Springs annually to bathe in the waters at the Buckstaff Bathhouse, which has run without interruption since 1912, and the Quapaw, a historic bathhouse now operating as a spa, as well as at historic local hotels like the Arlington. Many journey to the park just to drink the thermal water, accessible at jug fountains.

Bathing was interracial before the passage of Jim Crow laws, but after, things changed dramatically. Hill has, in the past, employed a character actor to tell the story of a Black bathhouse employee named Katie Tate—Hill intends to revisit this approach as well as to install more sculptural mannequins once tours resume again.

“It gets the points across—[Katie Tate] could only eat lunch in the basement, only when she had no customers, and after work she couldn’t ride on a streetcar if there was not a seat in the back, per the ‘Streetcar Act,’ so she may have to walk home,” he explains.

Local, socially distanced centennial events began on March 4 and extend through November, and virtual content and experiences via the park’s social media accounts, like a monthly and themed photo contest, will be ongoing as well. Beyond downtown, trails tuck into the mountainous interior, and dirt paths weave uphill. The 13-mile Sunset Trail loops up, down, and around the mountains, through deciduous and piney wood forests, and into remote places where you only see one or two other people. At every turn, the views are different. Waymouth describes it as “really far removed and then you get to these clearings where off in the distance you can see the top of the Arlington Hotel or you can see the Hot Springs Mountain Tower and your like oh wow, this is all still here—your connected and disconnected at the same time. It gives a great sense of everything that the park protects.”