Each Valentine's Day, couples flock to pray at a 1,300-year-old Osaka shrine linked to romantic tragedy, the Japanese equivalent of Shakespeare’s renowned tale of love found and lost.

Ohatsu Tenjin Shrine is the spiritual home of Ohatsu and Tokubei, perhaps Japan’s most famous fictional couple. They are the lead characters in the Love Suicides at Sonezaki, a 300-year-old play that was inspired by a heartbreaking true event that took place at this same shrine. Originally it was written as a Bunraku puppet theater performance. It has since been adapted in countless stage plays, songs, poems, movies, TV adaptions, and animated features.

While Valentine’s Day has only been observed in Japan in recent decades, the story of Ohatsu and Tokubei has been enthralling couples since 1703, when it was first performed. It was written by Chikamatsu Monzaemon in response to a tragedy that occurred in Osaka that same year. On the grounds of the Ohatsu Tenjin Shrine, priests found the bodies of two lovers who had committed suicide due to the nature of their forbidden relationship. They died together so their romance could exist in eternity.

In the play Love Suicides at Sonezaki, Tokubei is a sales manager at a soy sauce factory and Ohatsu is a sex worker. Years after being romantically involved, they meet by chance at Ikutama Shrine, a real location in Osaka. Ohatsu is angry at Tokubei for not staying in touch, but the man explains he has been through a difficult period in his life. They rekindle their relationship, which must exist in secret due to Ohatsu’s occupation. Soon, Tokubei faces a dilemma. He works for a factory owned by his uncle, who says Tokubei will inherit this business if he agrees to marry a niece of one of his associates. When Tokubei refuses, due to his love for Ohatsu, his uncle becomes livid and seeks revenge.

Recommended Fodor’s Video

He fires Tokubei, kicks him out of his house, and demands he immediately repay a loan. Tokubei is then scammed by a close friend. This man begs to borrow the money Tokubei intends to use to clear the debt with his uncle. The friend later denies Tokubei ever gave him this money and then assaults Tokubei in front of a crowd, causing him immense shame. Humiliated, homeless, and unemployed, Tokubei decides he should take his own life, which in that era of Japan was seen as an honorable death, often performed by Samurai in what was called Seppuku or Hari-Kari. He tells Ohatsu that he wants to live by her side forever, and she agrees to join him in the afterlife. They enter a forest, tie themselves to a “magic” tree that has two species of trees intertwined, and look in each other’s eyes as Tokubei kills Ohatsu and then himself.

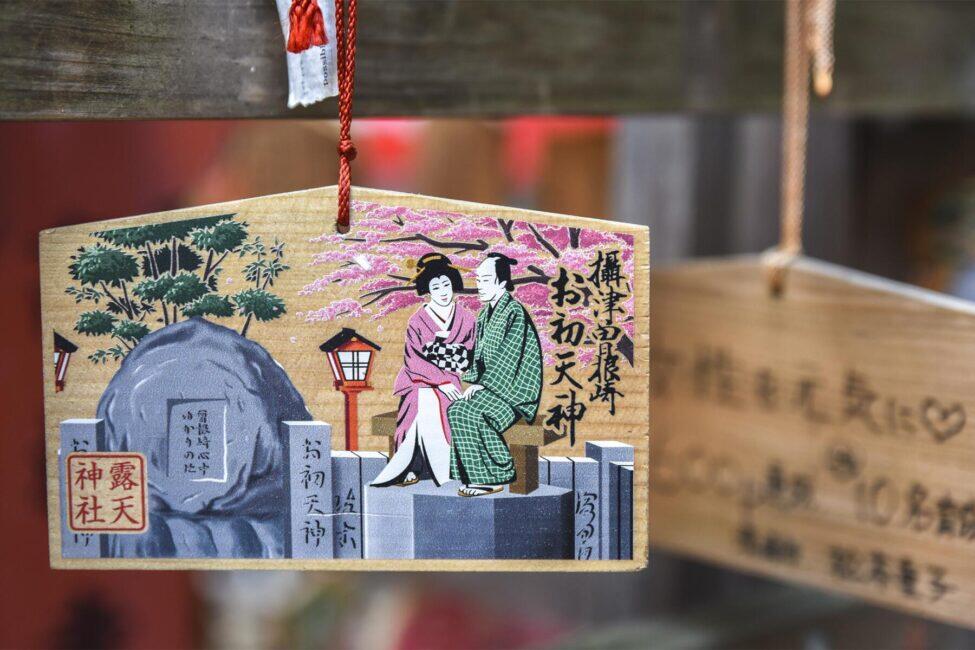

This tale continues to have a significant impact on Japanese culture, attracting many couples to Ohatsu Tenjin to contact the Shinto gods. Their prayers are transported by Mother Nature: When the wind pierces this shrine, it disturbs a cluster of dangling plaques and carries the written wishes they bear up and away to the deities. They include longings for companionship. Appeals for romantic faithfulness. Yearnings for a successful pregnancy. These emotional requests, penned by the worshippers who hang the small wooden plaques, are read by one of the shrine’s priests who then includes them in his own prayers.

The plaques are called Ema. Japanese people have used them for more than 1,000 years as a means of conveying wishes to the country’s Shinto and Buddhist deities. Tourists to Japan will see them hanging from racks in the majority of the country’s more than 100,000 Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines. Foreigners, too, are free to write their own prayers on Ema, which can be bought at these religious sites for about $4 each. Typically one side of them is left vacant for written wishes. The other side is often decorated with symbols connected to a particular type of prayer, as some shrines and temples in Japan are linked to a theme, such as educational success, financial prosperity, or long life, and attract worshippers asking for those things. At Ohatsu Tenjin, most of the hundreds of Ema on display are embellished by icons of passion. They’re variously adorned by love hearts, couples embracing, and romantic settings like cherry blossom forests, majestic mountains, and pristine lakes.

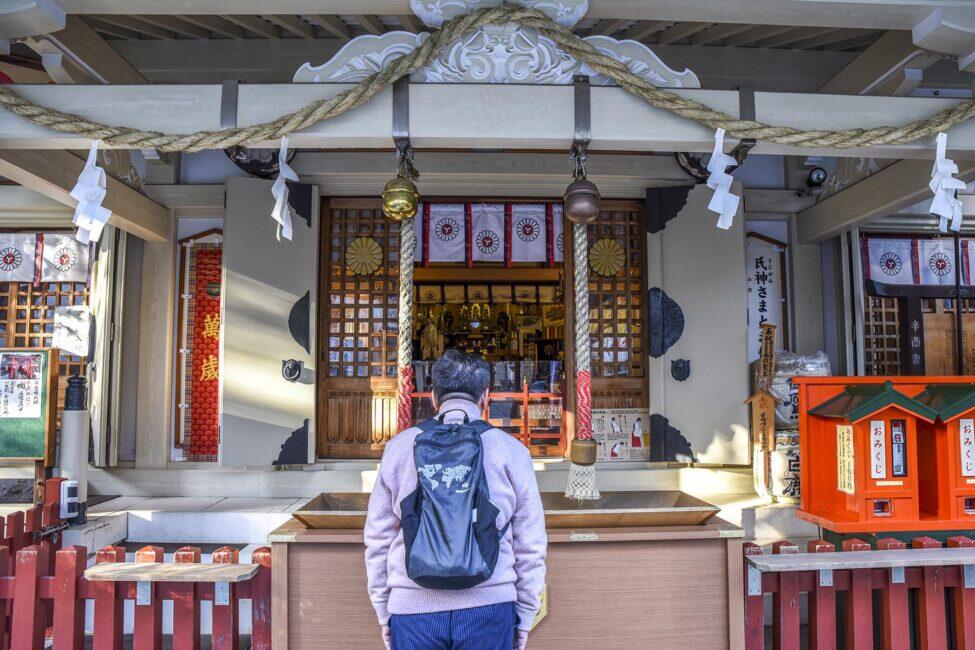

This shine is busy with visitors throughout the year due to its deep history, attractive grounds, and prominent location. Perched in the heart of downtown Osaka, Ohatsu Tenjin sits behind skyscrapers on the path between the commanding Osaka Castle and the city’s gigantic main railway station. It is within 15 minutes’ walk of many of Osaka’s key tourist attractions, including the National Museum of Art, the Umeda Sky Building, and Nakanoshima Park.

But the shrine’s two biggest days of the year are February 14 and March 14. That’s because in Japan, Valentine’s Day is celebrated a bit differently than in Western countries. On the first of those days, it is women who give gifts to their male partners, before the men return the favor on March 14, which is known as White Day.

The ending of Ohatsu and Tokubei’s story is undeniably grim, but the concept of immortal passion is what has made the story of the Love Suicides at Sonezaki so enduring in Japan. This February 14th, many Japanese couples will pass through the red gate of Ohatsu Tenjin Shrine. For Valentine’s Day, they’ll say prayers and hang plaques wishing for their love to last as long as Ohatsu and Tokubei’s.