“The gorgeous peacock is the glory of God.”

For well over 2,000 years, peacocks have pranced through the arts, architecture, legends, and religions of India. From the Peacock Throne of Shah Jahan, where two peacocks facing each other topped columns made of emeralds for the 17th-century Muslim emperor who built the Taj Mahal for his dead wife, to the Peacock Gate at Jaipur’s City Palace in Rajasthan, where peacocks, tails gorgeously fanned out, top an 18th-century gate to a courtyard, to a temple shaped like a peacock’s tail in south India, peacocks prevail.

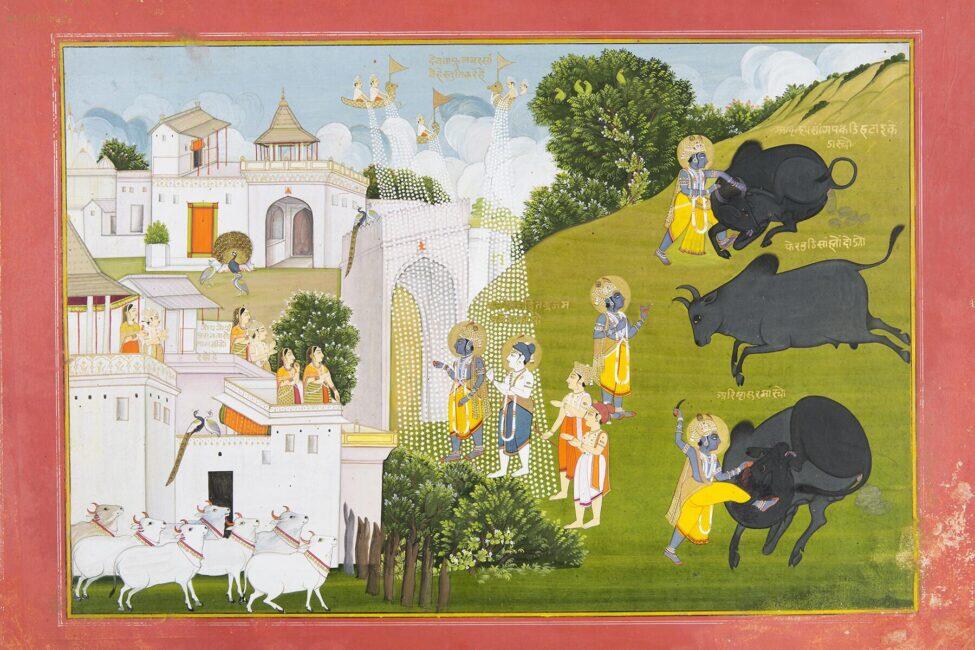

The most beloved Hindu god, Lord Krishna, wears a peacock feather in his crown. A legend says peacocks were so enchanted by his flute-playing, they laid their feathers on the ground before him, and he promised to wear them forever. The Hindu god of war, Kartikeya (also called Murugan or Skanda), uses the peacock as his vehicle in many depictions in south India. Saraswati, the Hindu goddess of wisdom and music, is often depicted with a peacock in south India (a swan elsewhere).

Another legend explains the origin of the peacock’s magnificent plumage. When Indra, the Hindu god of rain, thunder, and lightning, was fighting a demon-king named Rayana, a peacock raised its tail to form a shield to protect him from view. As a reward, peacocks were given glorious blue-green feathers.

“The gorgeous peacock is the glory of God,” a Sanskrit verse says. “In a country of pageantry and color, it is only fitting that the peacock has been officially proclaimed as the national bird of India,” wrote E.P. Gee, a British wildlife photographer in The Wild Life of India in 1964.

Recommended Fodor’s Video

“The peacock has been a potent symbol in Indian art across different time periods, genres and mediums, from its earliest traces in painted prehistoric rock shelters and sculptures in the Indus Valley Civilization [2,500-1,500 B.C.] to Mughal miniature paintings to today,” says Kamini Sawhney, director of the Museum of Art & Photography in Bengaluru (Bangalore). “Peacocks are in Hindu epics like the Ramayana and Mahabharata and the Rigveda, India’s oldest sacred text [written around 1,500 B.C. in Sanskrit].”

A Hindu dynasty whose emblem was the peacock was even named for the bird. The Mauryan Empire, which was founded in 322 B.C. by Chandragupta Maurya, was called the greatest empire in ancient India; it once stretched from Afghanistan to Bengal, and from Kashmir to the Deccan plateau. Mauryan himself was raised by peacock-tamers, some sources say. The later Gupta dynasty depicted a peacock, and the king feeding a peacock, on gold and silver fourth- and fifth-century coins.

Once you start looking for peacock art and monuments in India, you find them everywhere. Okay, Shah Jahan’s Peacock Throne is gone. Encrusted with diamonds, sapphires, and pearls, the masterpiece that took seven years of labor ended up in Persia, stolen in 1739 by the conqueror Nadir Shah along with other palace treasures when he ransacked Delhi, carried by elephants and camels. Later, it was destroyed, chopped up for its precious gems. But don’t worry: peacock motifs are endless.

Museum of Art & Photography (MAP), Bengaluru

“In South India, the Basadi Betta temple in Karnataka, Kartikeya mounted on a peacock on a temple wall at Sri Meenakshi temple in Madurai [in Tamil Nadu], and the Hampi ruins in Karnataka stand out. Kartikeya is worshipped mostly in south India, so depictions of him on his peacock are very popular there, particularly in Tamil Nadu state but Kerala and Karnataka, as well,” says Monisha Bharadwaj, author of India Style, a book on design, and owner of a cooking school, Cooking with Monisha.

The peacock tail-shaped, aqua and gold Basadi Betta temple is in the rural Mandaragiri Hills, a two-hour drive from bustling Bengaluru; it’s designed to look like the peacock feather fans carried by monks in the Jain religion. Sri Meenakshi is an exuberantly colorful example of South India’s Dravidian-style architecture, where the god of war sits astride a peacock in profile on a bright-blue tower wall. Impressive ruins near the village of Hampi are of Vijayanagar, once the capital of one of India’s biggest Hindu empires until 1565, when it was conquered.

“Some legends claim that the Buddha was a golden peacock in a previous birth, so the bird is considered sacred to Buddhists, too. There are stone carvings of peacocks at the Sanchi stupas commissioned by Emperor Ashoka in the 3rd century B.C.,” she adds. The Sanchi towers, one of India’s oldest stone structures and a UNESCO World Heritage site, are a Buddhist complex built by the Mauryan emperor Ashoka, an avid convert, near Bhopal in Madhya Pradesh state. Buddhism was born in India: the Buddha was a Hindu prince who gained enlightenment after sitting under a bodhi tree in Bodhgaya.

Museum of Art & Photography (MAP), Bengaluru

To see a potpourri of peacocks in one place, the museum in Bengaluru, India’s top technology capital, is a great place to start. Its collection ranges from a painting where Krishna defeats a bull-demon and peacocks are celebrating, to lamp tops and painted textiles used at shrines to brocade saris and skirts. “Peacocks are associated with royalty and grandeur, so you often encounter their imagery in many Indian textiles,” says Sawhney.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York has both a peacock-shaped lute, popular at 19th-century royal courts, and a Mughal miniature painting of a peacock and a peahen (female birds don’t have the glorious plumage).

Today, peacocks are a popular motif for rangoli (ornate round floor art designs made of colored sand or flour) during Diwali, the Hindu fall festival of lights to welcome Lakshmi (the goddess of wealth), into households. The bird is also a favorite motif for flower-petal rangoli—called pookalam—created for Onam in Kerala, one of the biggest celebrations in India’s southernmost state.

If you crave the real thing, more than 130 peacocks frolic in the gardens at Rambagh Palace, a luxury hotel and former royal residence in Jaipur. One, named Sultan, has reportedly taken a liking to a staffer and looks for him daily for cashew and almond snacks. The Taj Hotels Rajasthan property also has a Peacock Suite, bedecked with peacock motifs, marble inlay, and delicate mirror and stonework. Peacocks also roam the countryside and villages, and are so beloved, India’s Prime Minister shared a video last summer of him feeding the birds by hand at his official home in Delhi, and reciting a poem about them. It prompted swipes from critics that he picked peacocks over the pandemic.