The method behind this magical art is so closely guarded it’s been referred to as a “second-level state secret.”

A fan, hand, or cape passes across the performer’s face. In one second, presto! His elaborate makeup changes completely. It happens again and again, as the performer leaves the stage to mingle with the audience, who are frantically clapping and begging for more.

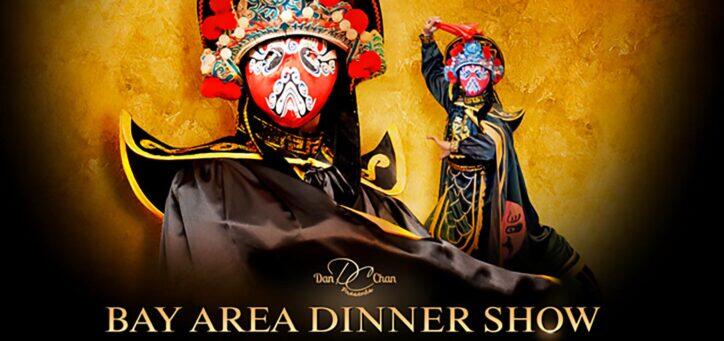

Called face-changing, it’s a magic trick that’s a staple of Sichuan Opera. Performers in vividly colorful costumes and ornate headdresses change masks in the twinkling of an eye. Nine or ten masks are common. Different colored masks signify different emotions, like anger, fear, and slyness. Called bian lian, it’s the most famous element in the opera style of Sichuan, the province famous for giant pandas and tongue-tingling Sichuan food.

Centuries before mask-wearing became de rigeur during the pandemic, this mask-wearing trick began about 300 years ago in Sichuan. Often, it’s performed in front of a backdrop that shows the different masks. A closely-guarded secret, traditionally handed down from father to son, it was named a “second-level state secret” by China’s Ministry of Culture in 1987. You’ll find replicas of the fierce-looking masks in shops all over Sichuan.

Recommended Fodor’s Video

In Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan province, it’s part of every Sichuan Opera, which also features acrobatics, high-pitched singing, shadow puppetry, and live music. “The main places to see it are Shufeng Yayun, a teahouse in Chengdu Cultural Park and Fu Rong Gui Cui, a theater,” according to Wild China, a tour operator with a U.S. office. Tea is generally included if you watch it at a teahouse, as I did. (At Shufeng, an added bonus is that you can have a head and shoulder massage during or before the opera.) Short half-hour performances of face-changing alone can also be found in Jinli Ancient Street, or the Wide and Narrow Lanes, a mélange of dozens of shops, restaurants, and tea houses. You buy tickets at the theater.

Bian lian is always accompanied by the same melodramatic song, an ode to the craft. “Quick as the wind, fast as lightning,” say the lyrics, plus a rapid staccato chorus of “Look, look, look, look, look, look, look/Change, change, change.” That lightning analogy is no joke. Magicians Penn & Teller called it “one of the most amazing magic things I’ve ever seen” during their Magic and Mystery tour of China, a 2003 TV special. “Don’t waste your time trying to bust this guy by taping the show and slowing it down…He’s just too darn good.”

You can also see it in other Chinese cities, like Beijing, during Chinese New Year and Autumn Festivals, and, if you’re lucky, in the U.S. I first saw it in San Francisco at a Chinese restaurant, Chili House, sitting inches away from a bian lian performer from China.

Dan Chan, a Bay Area magician who performs bian lian, calls it “one of the most difficult and demanding things I’ve done in magic.” Harder than pick-pocketing, mind-reading, and unlocking iPhones, he adds. Even harder than being sawed in half? “Being sawed in half—ha! That’s easy. You don’t even have to be a contortionist to do that,” scoffed Chan, who’s performed magic at Silicon Valley tech companies like Google, Facebook, Apple, and Adobe and for billionaires and companies around the world.

Asked what technique face-changing employed—misdirection, sleight of hand, illusion—he replies cryptically with one word: speed. “There are about 30 techniques in magic, but this is nothing more than speed.” He adds, “It’s more akin to martial arts than magic, extremely physically demanding. I usually take a month to train. I’ve hurt my neck and back doing it.” Most performers are drenched in sweat at the end.

“Each face represents a different character, and each assumes a unique gait, pose, and body posture,” adds Chan, who says just five performers in the U.S. and Canada do face-changing. He’s even performed the most difficult trick of all, hui lian: the mask, after changing, reappears in the blink of an eye.

Face-changing is so famous in China, a 1996 movie, The King of Masks, was made. (It’s on Amazon Prime and Kanopy.) It tells the story of an aging itinerant street performer in the 1930s, so eager to pass it on to an apprentice that he buys an orphan on the black market. A famous Hong Kong pop singer, Andy Lau, reportedly paid a master $360,000 USD to learn it.

It’s extremely unusual for a foreigner to learn the art. Chan, who is Chinese-American, learned it from a master in Malaysia, which has a big Chinese community. The day before his flight home to California, he read a newspaper article about a master in Kuala Lumpur. So, he returned to Malaysia a few months later. “After studying day and night for what seemed like a decade (but was actually a few months), I learned it.”

He’d love to teach it to his daughter, 11. He says. “I’ve done my son how to juggle three flaming torches. As an Asian-American, I’d be proud to pass on this ancient tradition to my daughter.”